What Is Culture, Really? Why WEIRD Psychology Doesn’t Explain the World

"Those who only know one country know no country." – Martin Lipset

You can read the Spanish version here.

What the Hell is Culture, Anyway?

First off, what is culture? Food, traditions, language, and so on, right? Well, yeah, but we need a better explanation than that at Born Without Borders. So, let's get a bit academic here and use Richerson & Boyd's definition:

Culture is any information acquired from other members of one's species through social learning that can affect an individual's behaviour. In other words, culture is any idea, belief, technology, habit, or practice we acquire through learning from others.

Even if you've never left the street you grew up on, you're still part of more than one culture. Cultures are people who exist within some shared context. So your school, workplace, gym, knitting club, S&M dungeon, abandoned warehouse rave crew or whatever it may be has a culture.

Is One Culture "Richer" Than Another?

So what the hell do people mean when they say things like, “The culture is so much richer here?” Do they mean that there are more ideas, beliefs, technologies, habits, and practices? Do they mean that there are more groups of people mixing?

Throughout my life, I've heard Canadians and Europeans say, "There's more culture in Europe than in Canada." Sometimes, they even say "North America," meaning the handful of cities they visited (usually not including those in Mexico). When I ask them what they mean by that, they typically mention that there's more history and language diversity—and not as many strip malls.

Saying that Europe has so much more history and language implies that Canada didn't have a culture till white folk came around. More than 70 indigenous languages are spoken across Canada, and Clovis sites dated 13,500 years ago were discovered in western North America. Now, you might argue that Europe has over 200 unofficial languages, and you can't really compare prehistoric Paleoamericans like the Clovis to, let's say, the Greeks. But I will say that many indigenous cultures were traditionally oral, so unlike Europeans, they didn't have everything written down to show "how much culture" they had. Also, Europe is a continent, and Canada is a country.

Now, if we're comparing continents, Africa has over 1000 languages and has the oldest civilizations to boot. But I doubt that I’m going to hear a Parisian say “La culture de Mombasa est tellement plus riche que la nôtre” (Mombasa’s culture is so much richer than ours) any time soon.

The point is saying one place has more culture than the other doesn't get us anywhere. From my experience, it usually leads to people talking about the museums, galleries, and landmarks they visited. As much as I enjoy learning about history and taking part in "high" culture activities, such as gawking at all the artifacts Europeans stole from Africa and South America, it's only a tiny piece of the puzzle for how to understand people and culture.

Understanding Cultural Psychology: A Hierarchical Framework

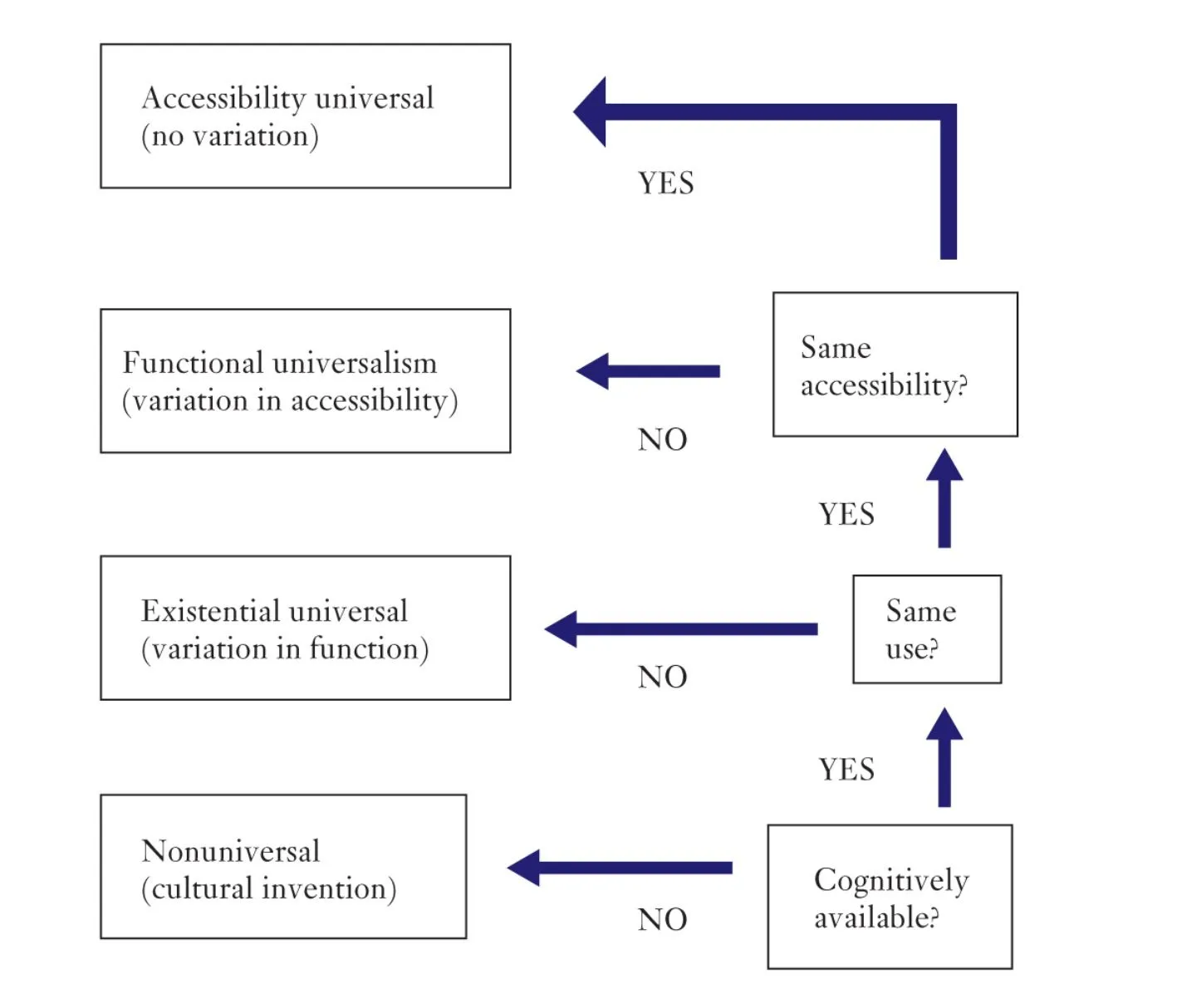

To figure out how culture shapes us and what psychological phenomena are universal, let's start with a hierarchical framework created by Steven J. Heine and one of my favourite professors, Ara Norenzayan.

Cool, cool, but what does this mean?

- Nonuniversal (cultural invention): A cognitive tool not found in all cultures. For example, an abacus is a calculation tool used in some parts of the Middle East and Asia. Users tend to favor the odd-even distinction, think in base units of five, and make a particular pattern of errors not seen in non-abacus users.

- Existential universal: A cognitive tool found in all cultures but serves different functions in different cultures. For example, Westerners tend to find experiences with success to be motivating and experiences with failure to be demotivating. In contrast, East Asians tend to show the opposite pattern, whereby they work harder after failures than after successes.

- Functional universal: A cognitive tool serves the same function in all cultures but is present in different degrees. For example, one large-scale investigation explored whether people from various subsistence societies around the world tended to punish those who acted unfairly, even if that punishment was costly to the individual. Among the Tsimane of Bolivia, participants spent up to 28% of their earnings to punish others who were unfair. In contrast, among the Gusii of Kenya, participants spent more than 90% of their earnings. Then there's me; I don't think I'd spend any of my earnings to punish anyone—to rehabilitate and teach is a different story.

- Accessibility universal: A cognitive tool equally accessible and serves the same purpose across all cultures. For example, social facilitation—the tendency for individuals to do better at well-learned tasks and worse at poorly learned ones when in the presence of others—has been shown to occur in insects and humans.

The Müller-Lyer Illusion & The WEIRD Problem

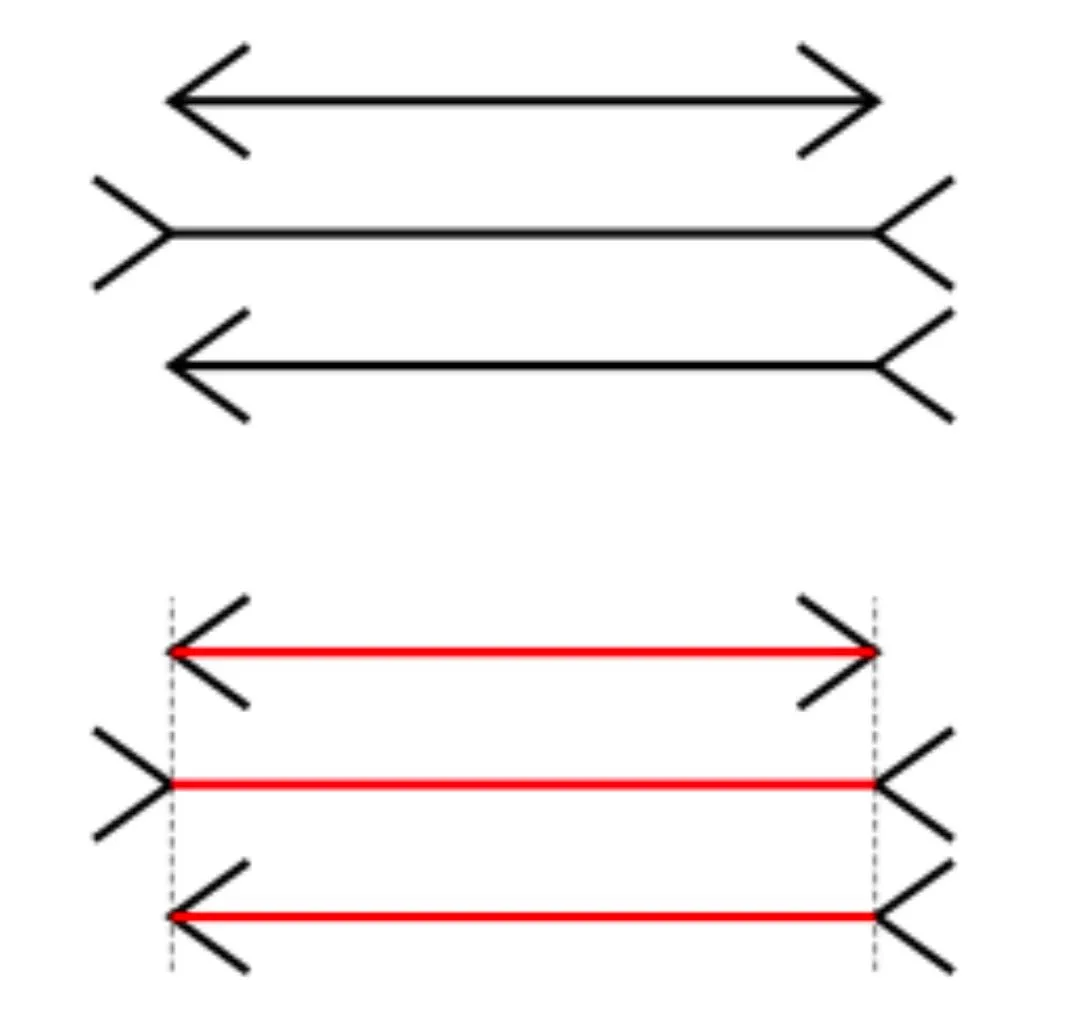

Now, let's take a look at the Müller-Lyer illusion.

Would you assume this illusion is universal, or does our culture affect how we see it? I'll give you a hint—people from foraging societies don't see the illusion. Why? Take a moment to think about it.

(Drum roll)

If people aren't exposed to carpenters' corners as children, they don't learn that the corners provide depth cues and are not susceptible to the illusion. Now, you might be thinking that's pretty weird. But it turns out you might be the weird one.

Google WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic), and you'll find a bunch of information from Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan. Fun fact, this research ended up on major news outlets such as the Atlantic, and Norenzayan told me that they came up with the acronym while shooting the shit. Of course, he didn't actually say shooting the shit, but something along those lines.

What's the problem with WEIRD people? Well, WEIRD people are often louder, more expressive and give more extreme responses. In other words, WEIRD people don't represent the world (even though we often think we do). Approximately 70% of all psychology study participants are undergraduate students, meaning a randomly selected American undergraduate is more than 4,000 times more likely to be a research participant in a psychology study than a randomly selected participant outside of the West. So, next time you pick up an article that states STUDY SHOWS (INSERT CLICKBAIT), remember that it's likely not a universal truth.

Practical Methods to Understand Cultural Influence

Okay, a lot of research is weird; I get it. But aside from the hierarchical framework, how do we figure out how culture influences and shapes us?

Well, unless you're a researcher, you're probably not too interested in setting control groups, using back-translation methods, standardizing your data, setting up between and within-groups manipulations, situational sampling, and all that jazz. By the way, if you are, please comment to get a discussion going.

However, travelers and people interested in culture need to understand some psychological underpinnings and methods to form more accurate opinions. Here's a list to get us started:

- Pluralistic ignorance: The tendency for people to collectively misinterpret the thoughts that underlie other people's behaviors. For example, in college student samples, people believe their peers are more interested in "hooking up" than they are and that people hold more politically correct beliefs than they do. Now, I don't know if that's still true in 2022, and from personal experience, I doubt it, but then again, I might be pluralistically ignorant. The point is, don't believe everything people tell you.

- The same same, but different method: Okay, I made this up, but as Heine mentions in his book Cultural Psychology, if you're interested, for example, in understanding how collectivism shapes how people view their relationships, you should visit two cultures that vary in their degree of collectivism.

- Read, but also don't: Okay, another term I pulled out of my ass, but again, Heine mentions that reading ethnographies are great for complementary information, but keep in mind that ethnographic observations are filtered through the ethnographer's own beliefs, biases, and values.

- Acquiescence bias: The tendency to agree with most statements. In other words, don't put words in someone's mouth, especially if they come from an East Asian culture, because they have a more holistic way of looking at the world, which means there are more possible truths.

- Reference-group effect: Different cultures tend to evaluate themselves by comparing themselves to different reference groups/different standards. For example, one study during the civil rights movement found that African-American soldiers in the North were less satisfied than those in the South because they compared themselves to civilian African-Americans who were better off in the North than in the South. Here, the reference-group effect leads one to the exact opposite conclusion—Southern African-American soldiers were better off than Northern ones.

- Deprivation effects: Who values enjoying life and pleasure more, East Germans or Italians? Man, think about the patios, the time spent eating and soaking up the sun–the answer is obvious. Well, it turns out that East Germans scored the third highest of all countries on this dimension, while Italians scored the second lowest. Another study found that Americans value "humility" more than the Chinese, whereas the Chinese value "choosing one's own goals" more than Americans. Are you confused AF right now? I was when I first read this. One way to make sense of this is to consider what people actually have compared to what they would like to have. So, again, don't believe everything people tell you.

Understanding Beyond the Surface

Well, there ya have it, folks: an introduction to cultural psychology and how to think about culture more fruitfully. I hope these few examples show how culture is far more than traditions, museums, customs and language. Culture shapes how we see the world and understand ourselves. We are all subject to illusions, biases, and other psychological phenomena. Hopefully, awareness of some of these will help us better understand ourselves and each other. If any of you were too lazy or rushed to read all of this, I'll try to sum it up with one quote.

"Those who only know one country know no country." — Martin Lipset

Ready to See Beyond Your Borders?

If you want to understand people across borders — or navigate cultural identity, language shifts, and moving between systems — Born Without Borders is for you.

➡ Work with me on cultural, language, and fitness. I help people who live between languages, cultures, and systems find clarity, connection, and confidence in motion.

➡ Subscribe for fresh perspectives in English and Spanish.

➡ Or follow this blog via the Fediverse: @index@born-without-borders.ghost.io

Book a free 20-minute if you want to:

- Communicate across cultures

- Move to Spain & Canada without the sugarcoated lies

- Fitness for nomads & neurodivergent clients

Enjoyed this article?

If you believe in research and writing that break down borders, foster cross-cultural understanding, and inspire people to live unbound, consider becoming a paid subscriber to Born Without Borders.

All my work is published on Ghost, a decentralized, non-profit, and carbon-neutral platform—free from VC funding and the grip of technofeudal lords.

I don’t use algorithms to hijack your attention.

My work can only exist if you share and support it.

Need Coaching or English Classes?

- Unlock Your Authentic Voice (Across Cultures & Systems): If you're a multilingual professional or "cultural inbetweener" who feels unseen or misread, let's refine your English for nuance, confidence, and true self-expression.

Book a Class Today

Group Classes

Pairs (Two Students)

Preply Link

Affiliate Links for Global Citizens

- Home Exchange: Trade homes, not hotel bills. Live like a local anywhere in the world.

- Wise: Send money across borders without losing your mind (or half your paycheck in fees).

- Preply: Make a living teaching people worldwide.

- Flatio: A more ethical version of Airbnb.

Works Cited

- Heine, S. J. (2015, August 28). Cultural Psychology. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Census in Brief: The Aboriginal languages of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit. (2017, October 25).https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016022/98-200-x2016022-eng.cfm?ref=withoutborders.fyi

- Americans, O. S. U. C. F. T. S. O. T. F. (1999, January 1). Ice Age People of North America. Corvallis : Oregon State University Press for the Center for the Study of the First Americans.

- Tirosh, O. (2023, March 30). European Languages: Exploring the Languages of Europe. Tomedes.https://www.tomedes.com/translator-hub/european-languages?ref=withoutborders.fyi#:~:text=Europe%20is%20home%20to%2024,to%201,500%20to%202,000%20languages.

- Miller, K. F., & Paredes, D. (1996). On the Shoulders of Giants: Cultural Tools and Mathematical. The nature of mathematical thinking, 83.

- Henrich, J., McElreath, R., Barr, A., Ensminger, J., Barrett, C., Bolyanatz, A., Cardenas, J. C., Gurven, M., Gwako, E., Henrich, N., Lesorogol, C., Marlowe, F., Tracer, D., & Ziker, J. (2006). Costly punishment across human societies. Science (New York, N.Y.), 312(5781), 1767–1770.https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127333

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13(2), 83–92.https://doi.org/10.1037/h0028063

- McCauley, R. N., & Henrich, J. (2006, February). Susceptibility to the Müller-Lyer Illusion, Theory-Neutral Observation, and the Diachronic Penetrability of the Visual Input System. Philosophical Psychology, 19(1), 79–101.https://doi.org/10.1080/09515080500462347

- Igarashi, M., Hatsuyama, Y., Harada, T., & Fukasawa-Akada, T. (2016). Biotechnology and apple breeding in Japan. Breeding science, 66(1), 18–33.https://doi.org/10.1270/jsbbs.66.18

- Van Boven, L. (2000). Pluralistic ignorance and political correctness: The case of affirmative action. Political Psychology, 21(2), 267–276.https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00187

- Tuddenham, R. D. (1948). Soldier intelligence in World Wars I and II. American Psychologist, 3(2), 54–56.https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054962

- Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? Journal of Social Issues, 50(4), 19–45.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb01196.x

- Peng, C. Y., Graves, P. R., Thoma, R. S., Wu, Z., Shaw, A. S., & Piwnica-Worms, H. (1997). Mitotic and G2 checkpoint control: regulation of 14-3-3 protein binding by phosphorylation of Cdc25C on serine-216. Science (New York, N.Y.), 277(5331), 1501–1505.https://doi.org/10.1126/science.277.5331.1501

Member discussion