The Running Mill

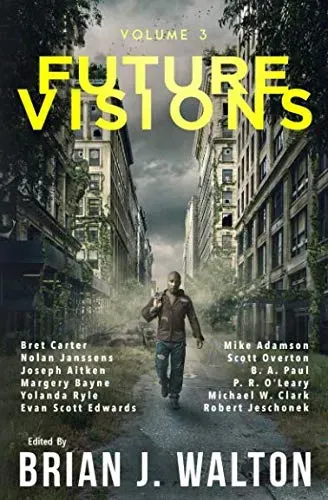

The Running Mill was initially published in Future Visions. This is a re-edited version.

Now that Trump and Elon Musk run ‘Merica, I thought it would be a perfect time to repost The Running Mill.

July 31st. Run.

Ricky was no longer grateful for the filtered air. Even when X-Up, his morning amphetamine drink, wore off, Ricky never slowed down; he just kept running, producing energy for the world.

The treadmills, bikes, ellipticals, and rowing machines are aligned in tight rows for ultimate efficiency. All the equipment was attached to batteries that Celta Corp later sold to various manufacturers worldwide. The harder the employees exercised, the more kilowatt-hours of energy they produced.

Compressed air like Norwegian Mountain Fresh and Canadian Crisp was pumped through the vents when workers collectively exceeded their monthly target of producing fifty thousand kilowatt-hours of energy. However, even the deliciously compressed air first sold to the Chinese elite and now to the American running mills couldn’t motivate Ricky to stay. But who else provided so many jobs? Solar, wind, and geothermal sure didn’t.

Ricky jumped into what he thought would be his last mandatory ice bath at the end of his shift. He said it was like a thousand illusory pin needles poking at his skin, but it healed his overused body. That day, he produced over eighty-kilowatt hours of energy, more than anyone else at the mill. Best of all, he wasn’t genetically modified.

The first-world youth had grown tired of a society filled with robotics, genetic modifications, virtual realities—you name it—they missed the outdoors, the air that was free. The youth needed an idol.

And I was going to give them just that.

When Ricky arrived at his small, decrepit apartment, his brother lay passed out on the couch, shirtless, heart beating against his ribcage. Ricky woke him with the smell of microwaved apple pie. Wherever there were electronics, I was watching.

“What’s the special occasion?”

“Leaving tonight, remember, Steve?”

“Yeah, yeah.”

“Take a bite of the damn apple pie.”

“I’m burnin’ less calories; I get less food. Way it is.”

“We’re not spendin’ another day here, aight.”

“I told you, I’m not cutting the damn tracker out of my arm.”

“The smuggler’s demands, Steve.”

“You know how deep that tracker is? We’ll get gangrene or some shit.”

“Eat the damn pie. We’re getting out of here.”

Ricky remembered every word of that conversation.

August 1st. Sell.

Together We Are Winners was the lie I saw or heard every morning. The new Rudas slogan was everywhere: the walls, the shirts, the shoes, the managers’ speeches, the bathroom stall walls—everyone at the Copenhagen headquarters loved it.

I worked in the communications department, where I was recently put in charge of finding influencers at the Cleveland, Ohio, Running Mill from Celta Corp (our parent company—not that anyone knew).

We got all the latest C-Web contact lenses, tatted finger C-r8s, and whatever else we needed to bring the internet to virtual reality. We could work anywhere and on any surface, yet I always had to come to work.

“Team Creativity” was the reason the managers gave us, but we didn’t have any creative input—that was left to the design team. Anyway, we got all the equipment for free—well, it seemed free until you read the privacy policy. But who the hell has time for that, right? Our job was to email partners and, mostly, to go through social media accounts looking for influencers. We were constantly stalking people, and the company ensured we were completely comfortable doing that. Our department had shared C-Display roundtables, modern upholstered chairs, showy lamps, an espresso machine—you know, the corporate life necessities.

Socrates said the unexamined life is not worth living. Well, we examined your life for you, and the number of followers determined how much your life was worth. Examine, analyze, predict, and use. Everything people posted to social media from their C-memory, I could later experience for myself. I could smell, taste, hear and feel everything they did. But I wanted more.

“Jet, get in my office,” shouted Christine from across the room.

With anyone else, she would have politically patted them on the shoulder and escorted them back to her office, but not with me. No siree. Good ol’ Jet needed to be humiliated in front of everyone.

“Hacking into home appliances, Jet. Really?” said Christine the second I stepped inside her office.

She fashioned her hair in a complicated bun with subtle pink streaks. As usual, she wore the most minimalist Rudas sports attire, but colour-coordinated and worn in such a way that she would look trendy no matter where she went.

“I had to. That guy, Ricky, he’s the only worker that runs fast enough to be an influencer. Plus, he’s not modified. And we need someone that isn’t modified to sell the natural counter-culture image,” I said.

“And you had to spy on him from home appliances to prove this to me?”

“Yes, the guy doesn’t have much of a social media presence.”

“It’s illegal.”

“Illegal-ish.”

“Yeah, well, maybe he felt spied on, and that’s why he just cut the damn tracker out of his arm.”

“I know.”

“Excuse me?”

I knew where he was heading. I knew he wanted to go where his brother could afford healthcare. I knew—I needed—him to come here.

I couldn’t go back to the USA. Three kids on the wage I made back home... they’d end up working part-time at a Running Mill.

August 2nd. Escape.

Ricky and Steve headed northeast, away from what was once the Golden State and towards Maine with not much more than a few nutrient bars and a flask of bourbon for Steve. When the tank was almost empty, Ricky stopped at the nearest gas station on the side of a desolate road. He sold his piece-of-shit car to the gas station clerk for three hundred bucks. He could have made three times that, but he didn’t have time to negotiate, and they needed to make sure the police couldn’t find them. Nobody was to leave the country illegally.

What Ricky didn’t know was that the second you cut your tracker out, the Sniffers (genetically modified police dogs) automatically came your way.

Ricky and Steve had been walking for an hour in Maine's humid East Coast air, and the sniffers were no longer far behind. One sniffer for Ricky, one for Steve, and one for who the hell knows—good luck if you can call it that.

I saw the brothers through the lenses I hacked. Steve was already leaning on his brother, suffering from the pain in his bad knee. The second they were in sight, the sniffers ran full speed towards them. Steve was the first to notice, and I could see that he was screaming, “Run.”

Ricky didn’t run. The idiot. He grabbed a stick, hopelessly fighting the sniffer that had latched onto Steve. The other two sniffers leaped and brought Ricky to the ground. The brothers lay there, frantically trying to scramble away from the dogs. Slowly, their frantic moves turned to sluggish, desperate swings. I was about to look away from my C-screen when a beat-up pickup truck ran the dogs over. Call it deus ex machina, if you will, but my marketing talents can’t orchestrate everything.

The brothers didn’t need to tell the man they were mill workers looking for a new life; the blood-soaked cloths wrapped around their arms said enough. The next few hours were silent; Ricky had no energy to speak. Ricky peered outside at the American wasteland, vast stretches of infertile lands that were once rich with produce. However desolate and ruined the land may have been, Ricky couldn’t help but realize that he would miss this great country he had always called home.

When Steve finally murmured unintelligible words, the man (who Ricky would later tell me was from Yemen) handed Steve a sweet, flaky pastry, probably Bint Al-Sahn. Steve slowly ate the pasty without saying a word.

“You will need to eat more if you are gonna survive the voyage.”

“What’s keeping you here?” Ricky asked.

The Yemeni man didn’t answer. He drove them for another few hours to Baldhead, Maine. When he dropped Ricky and Steve off, all he said was, “You won’t forget the smell.”

Ricky told me he easily found the corner store address to meet the traffickers. When I asked him how the voyage went, he couldn’t say a thing. Some tragedies can’t be voiced. Fortunately, my daughter told him about the art of poetry.

August 3rd to August 18th. Voyage.

We’re touching and sweating and crammed. Warm bodies at sea.

His musk, an overripe orange with garlic like father’s. He’s here with me.

Breath like sour apples, always cloaked in smoke. Was it like mom’s?

We’re hungry and touching and sweating and crammed. Warm bodies at sea.

His scrawny arm hides stories and wraps around my shoulder. He’s here with me.

Blistering bodies. Piss and shit on our legs. Too nauseated and frightened to care. Cold bodies at sea.

Ammonia wafts from his pores. Acid on his breath. His head lays on my shoulder. He’s here with me.

Cold bodies. They’re rotting and blue and tossed overboard. Forgotten at sea.

His tangy musk. His decayed smell. His fruity breath. His final breath.

Only remembered by me.

Thanks to me, that poem would receive over a hundred thousand likes and sad faces.

August 18th. Arrive.

I could have been working, relaxed, in Ruda’s new organic coffee bar where the milk was never dairy, and baristas always had dreadlocks or some culture-appropriated way of fashioning themselves—you know, the types of places you see on every block in every affluent city. But no, there I was, doing work on the shitter like I did every morning that week (to “time manage” and avoid distractions) when I received a text from my wife.

Courtney 6:30 am

This American Refugee apparently just outran a couple of police hounds. I just ran his tests at the hospital, and he’s not even modified. Think it’s Ricky?

Me 8:30 am

Was he part of a mill?

Courtney 8:32 am

We don’t know. Looks like he cut out his tracker. Cops heard that someone was smuggling over that new 3C-I drug ravers take, and they pulled over the wrong boat—prlly some setup. Anyway, this refugee’s in the boat, sees the cops and books it. Later on, they found him passed out and brought him here.

Me 8:35 am

Must be Ricky. I’ll head straight there.

Courtney 8:36 am

All the nurses here love him. He’s pretty sexy in an I’m broken and tough sort of way.

Courtney 8:36 am

*You still my sexy muffin man.

Me 8:37 am

Ha...Can you keep this on the DL? I need to get to him first.

Courtney 8:36 am

Sounds good.

Me 8:37 am

Love you.

Courtney 8:37 am

Love you too. Ps, are you texting on the toilet again?

Me 8:38 am

;)

When I got to the hospital, his mind had faded to an incoherent dust. He formed simple sentences interlaced with murmurs that rumbled from his stomach. At times, he would scream and beg for someone to come back. I thought he was just going mad from the pain—at the time, I didn’t know he was calling out for Steve.

When I asked the doctor what was wrong, he said, “Den veed bedst hvor Skoen trykker, som har den pas.” Directly translated, it means no one knows where the shoe pinches but he who wears it. Really, it means that nobody can fully understand another person's hardship or suffering. Whatever. As long as the doctor fully understood how to deal with malnutrition and severe sunstroke, Ricky would be okay, and so would my plan.

When Courtney and I brought Ricky home from the hospital for dinner, I could finally get to know him without hacking into his electronics, staring at him from his treadmill, and, well, you get the point. I could finally get to know him the old-fashioned way—I went straight to the liquor cabinet.

Ricky gulped down his gin-and-tonic and ravaged his food, the unchewed rye bread only making it down his gullet because he covered it in lard. Maybe I should have told him the mackerel still had bones, but I don’t think it would have made a difference. When Ricky first looked up from his plate, my children were already staring at him, and the food smeared across his face.

“You’re like a doggy,” said Ria, the oldest. “Maybe a Pit Bull or a Rottweiler.”

She was the only one of my children who didn’t seem intimidated by Ricky’s tatted arms and starved, hollowed face.

“That’s not the sort of thing you say to guests,” Courtney said. “Sorry, Ricky.”

“I meant the sort of Pit Bull with a nice puppy cross. Plus, I like all doggies,” Ria said.

“Me too,” said Eric and Julie in unison.

“Do you like doggies, mister?” Asked Ria.

“Sure... had a chocolate lab as a kid.” Ricky looked at me and said, “Do you have any whiskey?”

“No, sorry. Burns my throat.”

“I see. Well, could I have another one of these?”

“Of course.”

“Can puppies really be chocolate?” I heard Julie ask as I walked to the Kitchen.

“It’s the colour, dumbass,” said Ria.

I had to cover my mouth so nobody could hear me snickering in the Kitchen. Is it wrong to have a favourite child?

“Ria! Language. Don’t talk to your sister like that,” Courtney said, but I knew that she also wanted to laugh.

“I can’t help it that my sister has an IQ of a sea cucumber.”

“Cucumbers don’t grow in the sea, do they?” Julie said.

“Sea cucumber’s a marine animal,” Courtney said.

“Wow,” Ria said.

As I stood in the kitchen, I pictured how she likely shook her head in an overly dramatic way, pigtails swinging back and forth. Then I heard her say, “Do you have brothers and sisters, mister?”

“Where they’d go?” You can always count on children to ask questions you’re too afraid and conditioned to ask.

I entered the room and handed Ricky his drink.

“Were you the strongest one? Because I am,” Eric said.

“The brains, the bronze, and the bonehead,” said Ria.

“That’s enough, Ria,” I said.

“Sorry, Ricky... so you told me you lived close to Cleveland?” asked Courtney.

“Yup.”

“Originally from there?”

“Yeah, well, my Mom was from Grenada.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Why are you sorry, Mama?” Asked Julie.

“Because once the sea levels went up, all the small islands went bye-bye,” Ria said.

“Can you be any less sensitive, Ria?” Courtney asked.

“Are your feelings hurt, mister?”

Ricky just shook his head and glanced at Ria with a trace of a smirk.

“Why did they go bye-bye?” Asked Julie.

“They didn’t have the infrastructure to combat rising sea levels. Anyway, kids your age don’t need to know this sort of thing,” I said.

“I think we need to know all kinds of things. Like, why does my new friend have two mommies, but her one mommy doesn’t like to be called a mommy?” Ria asked.

“I think it’s time for you kids to go to bed,” Courtney suggested. “It’s getting late.”

“Yeah, I should hit the sack as well,” Ricky said, not making eye contact with anyone. One more drink, and maybe I would have heard his story sooner, but I knew all that I needed to know.

Later that night, I heard Ricky crying in the living room. I was about to check on him when I heard Ria’s tiny footsteps creeping down the stairs, her pace always slower and more controlled than her brother and sister. I walked out of my room to hear what she would say, but all she did was snuggle up next to Ricky and ask him to protect her from the monster under her bed. Ricky didn’t say a word; he just lay there next to Ria, the warmth of her frightened, small body healing him.

September 20th. Sponsor.

Ricky ran around the solar-powered racetrack, setting personal records and breathing fresh outdoor air. Ruda's headquarters was thirty minutes inland from Copenhagen, but even here, in the flat countryside, the subtle smell of sea lingered in the air—the canals were never far away.

When Ricky finished his final lap, he jogged toward us and let himself fall on the freshly mowed grass. He lay on his back, chest rising and falling, as he smiled, inhaling the fresh air. He closed his eyes, and for the first time, I saw him in bliss—an appreciation of the senses that no genetically modified athlete had ever shown.

He looked at me with his hazel-green eyes, slightly flawed and unsymmetrical, yet handsome and powerful. His emotions couldn’t hide behind perfected aesthetics. He showed us what everyone used to love about sports: the emotions.

What did viewers want more than emotions? Why did we have to turn the sport of running into a breakneck act? These were the sorts of questions I asked myself when I sponsored athletes and sent them out to run.

“Together We are Winners...” Ricky finally said.

“That’s right,” Christine said, turning off her contact lens camera. She got what she needed.

“I’ll run for Rudas under one condition.”

“And what’s that?” I asked.

“If I win the Celta Hi-Run, Celta has to move all their mills to smog-free cities.”

“That will never happen,” Christine said. “Nor do we have the power to make that happen.”

“Then I’m not running for you. I’d gladly work any other job here than support Celta Corp’s biggest event.”

I knew how to make him run for us; I just didn’t want to do it. Please, Ricky, I thought. Just give in.

“We’re trying to make a difference here, Ricky. People are starting to realize that our genetic modifications have homogenized us, not only increasing racial prejudices but now, the right disease could eliminate a whole population.”

Christine, such an incredible bullshitter. We didn’t care about disease, racial prejudices—we cared about trends, and the youth of today wanted something natural.

“I thought modifications got rid of diseases?” Ricky asked.

“They did eliminate some diseases. If we could just get rid of genes that cause diseases, that’d be great, but that’s not where the money is. The money is in the aesthetics and enhancements side of things, and where the money is, the people follow. ”

Oh damn, Christine. Good one, I thought.

“You’re the only person I know who stands a chance against genetically modified athletes. Especially if you stop drinking with Jet on Saturdays.”

“Why would winning a race change anything?”

“Because you’d be a symbol of the natural movement.”

“This natural thing... I don’t know. I don’t care about movements.”

“Then why’d you come here? To move somewhere where things are working, right?”

“Just a better alternative.”

Christine was a good bullshitter, but she wasn’t as desperate as me. Or maybe she wasn’t a conniving, heartless schmuck like me. No, I’m not heartless. I’m a good person. Good people do things for their families. Right?

“Listen, Ricky,” I said, knowing there was no turning back. “You’re from America, just like me. Remember when some people bought the virus that protected you from some pollutants?”

“What about it? It worked.”

“Did you get it?”

“Yeah, we all got it in school when we were younger.”

“Where are you going with this, Jet?” Christine asked.

“Check this out.” I displayed my C-screen on the ground in front of us. I opened a link to an article I found on some half-witted conspiracy website—Ricky didn’t seem like the type of guy who could differentiate between credible and non-credible news sources.

“Research shows that one-tenth of the population got an immune disease. Not a big deal for people who could afford the medication afterward, but it was a way for the government to wipe out certain populations.”

“Who made the virus?” Ricky asked, as I predicted.

“Same company as most modifications. Trazer. You need to insert a virus to destroy a gene that you later replace. It’s the same business,” I said. “And look, one of the geneticists came out and said that the company knew they were taking a risk all along.”

Ricky stared at the screen, his anger seemingly blinding him from the advertisement with a smiling white guru trying to sell some energy-healing bullshit.

“How was this legal? Why don’t more people know?”

“Things like this don’t stay in the news very long,” I said. Which, of course, wasn’t entirely true, but it sounded like something someone angry at the world would listen to.

When Christine looked at me, I couldn’t tell if she was flabbergasted or proud, maybe a bit of both. Either way, she didn’t look disgusted. My boss was a monster like me. Malicious and crude. Clever?

Ricky stared at the article and then suddenly started slapping himself across the face as he released the animalistic sounds I first heard in the hospital. I tried to stop him, well, I thought about stopping him—his slaps were frightening.

Tears poured down his face; I felt guilty, but not guilty enough. I never felt guilty enough. Ria would ameliorate his pain. They had been drawing and playing games with Julie and Eric for over three weeks now. Ria and Ricky were turning into the best of friends, and I provided that. Plus, I gave him food and a place to sleep. Maybe—maybe I didn't need to feel guilty. Right?

“Honey, what’s the matter?” asked Christine.

Ricky didn’t answer, but I knew what was wrong. He didn’t need to tell me his brother suffered from an immune disease. Ricky may have mostly discarded social media, but Steve sure did. A few depressing statuses and articles about Recolatus Immune Eating Disease were shared, and I knew everything I needed to know.

What I didn’t know was that Steve died in Ricky’s arms on the voyage here and that the smell of Steve’s rotting body lives on in Ricky’s nightmares. But do you know who he now calls in the middle of the night? Ria. My daughter. My creation. My doing.

Me convincing myself that I’m not a total schmuck.

November 22nd. Fame.

“You escaped from poverty three months ago, and already, you’ve won the Copenhagen Frisk Luft Marathon, the European Trail Run X, and now you’re about to enter the most watched race of all time,” said Chris Clark, one of America’s most esteemed talk show hosts via the C-web live interaction.

The host sat in his chair that he never seemed to leave, belly nearly bursting out from his thousand-dollar suit. Behind him, there were posters of all the famous people he had interviewed, including Denmark’s president and now Europe’s New Order leader, the woman who loved our slogan, Together We Are Winners.

“For the first time ever, you’ll be racing against the top runners in the world. And for the first time in four months, you, the most auspicious athlete to ever enter the Celta Hi-Marathon, will be returning to America. How does it feel, Mr. Zero to hero?”

“Well, I don’t know what auspicious means, but not great,” Ricky said.

Ricky’s skin now had a healthy glow, and the whites of his eyes were flawless. His Rudas casual wear fit perfectly on his sculpted body. He no longer looked like a mill worker; he looked like an influencer—the highest trending influencer for over a week now.

Ria sat next to Ricky on my living room couch, her rascally smile watched by millions. She put her arm around Ricky’s and said, “Auspicious means promising success, Ricky.”

“Well, it still doesn’t feel great.”

“And why is that?” Asked Chris, his voice crystal clear in my living room, a room which nearly a billion people were looking at on their C-screens.

“Celta Corp took advantage of me and people like me, desperate people in unlivable places.”

“Others might say that Celta Corp provides jobs and clean energy.”

“Chris, can I say something? Of course, I can say something. Here, we don’t use people. We don’t use modern-day sweatshops to provide power. We have the technology to provide a national base income. Here, everyone has the chance to use their talents to their greatest capacity,” said Ria.

“Or sit on their asses and live off hard-working people.”

“From your three chins, it seems you’ve been sitting on your ass too, Chris.”

“There she is, the famous feisty Ria, the twelve-year-old some say is a genius,” Chris said. “And why do you, oh so intelligent one, think Ricky should even race in the Celta Hi-Run?”

“Well, I’m probably supposed to say it’s because he can show the world you don’t need genetic modifications blah, blah, blah. But no, it’s because within the four months I’ve known Ricky Rivers, he’s become a brother to me, and I wanna see my brother kick some genetically modified ass.”

The refugee that integrates into the Scandinavian society—that’s a story that can sell. But a twelve-year-old girl who cures a refugee’s depression with her undisguised words and by giving him a chance to be a brother again—that story would triple Ruda's profits, and all Ricky had to do was wear our clothing.

“And what happens if you fail, Ricky Rivers? What will the world think of you and the natural movement then?”

“I damn well could fail. Unlike everyone else that’s always sucking up to me these days, Ria reminds me that the odds are very much against me. But there’s only one way I can fail the people that support me. There’s only one way I can fail Ria,” Ria laid her head on Ricky’s shoulder at that perfect televised moment, “and that would be if I didn’t run the race.”

“Well, Ricky, as much as we don’t see eye-to-eye on everything, I admire your spirit. Now, for my final question, the question many of our viewers have on their minds. Which nation will you be running for? The United States of America or The European Order?

“I will always be an American as long as my blood runs through my veins. America made me who I am, and I look forward to meeting my American supporters, but America is no longer my home.”

I came up with that for Ricky.

“But who will you be Running for then?”

“No one and everyone. I see no borders, the man-made lines that divide us. I will be running because I’m damn good at it.”

Ricky made it sound like something noble, but he was running for someone; he was running for Rudas, and it’s true, we don’t see borders—just like the Celta Corporation.

November 25th. Run.

Thousands stared down at Ricky Rivers, many with high hopes and others with disdain. Millions of others displayed their C-Screens on various surfaces all around the world: pubs, gyms, mud huts, churches, mosques—this was the race of the year. Ricky stood in the middle of the Los Angeles Running Stadium, one of the few places people could still breathe in the city that so many fled.

Norwegian Mountain Fresh emerged from the vents, filling the lungs of spectators and athletes alike—subtle hints of pine and wildflowers in the middle of the smog-ridden city of L.A.

People from all over the world filled the stadium. The older Scandinavians were always easy to pick apart from the crowd. A sea of blond hair and healthy faces. Some were proud to have Ricky Rivers living in their country; others felt he had betrayed them by not running for The European Order. However, the sea of blond hair only represented a small percentage of the people. There was another group of individuals that the marketer’s eye always picked out, and they were sitting everywhere with every nation—the people that saw no borders, the culture that spread across the world. You guessed it, the counter-culture youth—the natural movement. Everyone had their unique hairstyle and earthly coloured attire adorning their bodies. Some of their piercings resembled African tribes, while others’ accessories were hip and modern. They refused to be called homogenized. They refused to be called conformists. Anti-corporate, anti-establishment, anti-government—anti-everything but themselves.

Then there are the Chinese, the most prevalent population at any event. They were the first to invest in genetic medications and disregarded any laws other nations tried to implement. They were beyond curative modifications; they were the enhanced race. They all looked like stunning athletes, which explained why over half of the contestants Ricky was up against were Chinese. Even here, amongst the people where genetic modifications flourished, the counter-culture youth held up signs with Ricky’s name. To those that were modified themselves, it didn't matter that Ricky wasn’t. To root for Ricky was still cool.

There were ten racers. Six Chinese-born with genetic modifications, two Kenyans with a few “curative modifications” (curative seemed to have a broad meaning), a Russian that had competed for over a decade and didn’t age one bit, and then there was Ricky.

“Today is not just another race. Today is the day we see if humans have perfected the human genome. Today, we see if God has given us control of our destiny,” said the announcer, a Korean man with bleached skin and genetically modified cyan-blue eyes.

The crowd’s cheers turned to a pandemonium with the perpetual arguments of religion. The announcer kept babbling on, entertained by his own voice, and then finally:

“Racers, it is time to ascend to the treadmill.”

The athletes walked into the lift that took them up to a twenty-meter-wide treadmill. The treadmill was suspended several meters from the ground to ensure that when a racer could no longer keep up with the constantly increasing pace, they would fall and shatter their bones (the best way to market stem cell bone replacements). Once the last runner is left, the treadmill stops, and the race is over.

There Ricky stood, in the center of all the racers. He looked up at the camera and then took a piece of paper out of his pocket; on it was a drawing of Ricky and Ria sleeping in a grass field and dreaming about dogs and all the things that made them happy. Ricky then blew a kiss, folded the drawing, and placed it back into his pocket. That was when the horn sounded, and Ricky ran, just like he always did.

If you believe in research and writing that break down borders, foster cross-cultural understanding, and inspire people to live unbound, consider becoming a paid subscriber to Born Without Borders.

All my work is published on Ghost, a decentralized, non-profit, and carbon-neutral platform—free from VC funding and the grip of technofeudal lords.

I don’t use algorithms to hijack your attention.

My work can only exist if you share and support it.

- Become a Paid Member: Get access to all exclusive content and potentially included access to certain courses/workshops and directly support this work for just $5/ month or $50 / year.

- Become a Founding Member: For those who want to make sure I stay off the platforms causing mental illness, polarization, and a technofeudal shit show. Your deeper support makes all the difference for $30/ month or $300 / year.

Need Specialized Coaching?

- Unlock Your Authentic Voice (Across Cultures & Systems): If you're a multilingual professional or "cultural inbetweener" who feels unseen or misread, let's refine your English for nuance, confidence, and true self-expression.

Affiliate Links for Global Citizens

- Home Exchange: Trade homes, not hotel bills. Live like a local anywhere in the world.

- Wise: Send money across borders without losing your mind (or half your paycheck in fees).

- Preply: Make a living teaching people worldwide.

- Flatio: A more ethical version of Airbnb.

Member discussion