Forever Foreign

“Home is not just the place where you happen to be born. It’s the place where you become yourself.” — Pico Iyer.

Are you reading this in an email? I suggest clicking the link so you can read it on my website's cream paper texture.

The Key in Tierra del Fuego

Stories are the only inheritance I need.

Six dates—that’s all it took for my parents to elope in Jamaica. Since then, they wandered amid CIA shadows and sticky red tape, celebrated with the Sandanistas, dwelled on a monkey-ridden island with a beat-loving recluse, rose to the top of Tenerife’s tourist sector, dodged the draft, smuggled—

They unshackle the chains of conformity.

I’ve pleaded with my father to pen his tales throughout my life. The scrawled notes, remnants of rides to school, tipsy nights, and phone calls from youth to this moment weren’t enough.

‘Schrijf verdoemme oew verhoale op!"1

He told his stories in various languages, adding layers as he code-switched and retold stories from the perspective of different idiomas. I’d beg him to write the stories in Flemish, English, Spanish, or a mix of the three.

He never listened

… until now.

Cancer has a silver lining.

Luc/Luca/Lucas

Ekeren, Antwerp, 1967

The old globe, its faded colours weathered by time, sat atop the weighty marble stand next to the only cabinet with a key.

Papa didn’t need to lock the cabinet; he knew he was the only admirer of its contents, an ever-expanding collection symbolizing his ability to savour the moment instead of letting it get the best of him. It was a collection of fine whisky, cognac or Armagnac he regularly received as a gift after piloting a ship into Antwerp.

We were alone. It wasn’t Christmas, Easter, or a birthday—so why was he opening the cabinet?

Post a pour of spirits, he trailed his index finger the size of two markers over the Atlantic Ocean to the south of the American continent. The Belga cigarette's bluish wisps veiled the northern hemisphere in a gentle haze.

"I was second mate on the SS Louis Sheid when I sailed to South America for the first time. I believe it was in 1953. Europe was still completely under construction, and Argentina was the granary of the world at that time…and there was meat, lots of meat.”

He drew me near, and together, we gazed upon the globe as if a cinematic tableau unfolded before our eyes.

“We first sailed to Rosario, a city on the Parana River, deep inland, and then on the way back, we stopped in Buenos Aires.”

"And the country is called Argentina, right, Papa?”

My father's beautiful baritone voice ensured that the names of those exotic destinations were etched forever in my memory.

"Yes, Argentina. In Buenos Aires, I even bought two records with tango music by Carlos Gardel.”

It wasn't the first time I followed Papa's finger across the globe and greedily inhaled his stories mixed with the scent of tobacco. Even as a naive little brat, I knew two things I needed to survive: to breathe and to travel.

"Were you also here, Papa?" My little finger slid to the southernmost point of the American continent where the enchanting phrase "Tierra del Fuego" arced around an island.

"No, Lucas, I've never been there. That's the end of the world.”

The end of the world. At the time, I didn’t realize it would be the beginning of a new one.

“There's a big rock called Cape Horn where it's always stormy with waves as high as the church tower in Ekeren.”

I held my breath and tried to imagine how fire and stormy seas coexisted at the end of the world.

"That's where I want to go, Papa. I want to know why it's called Tierra del Fuego.”

Twenty-four years later, I found out and understood why this was a special day. I realized what the key truly unlocked.

Catalina

The rugged glaciers and towering snow-capped peaks surrounding the Beagle Channel used to give me a sense of peace, but not today. Nothing can take my mind off the Ushuaia’s landing strip—a neglected spec in the distance too short, even for the small plane.

“¿Podemos aterrizar?”2 My husband asks, his voice too high for me to believe the forced calmness.

30-knot winds toss the little plane from side to side until a sudden drop in pressure causes the plane to drop and my insides to rise.

“Depende,” says the pilot as we level out.

“¿Qué quieres decir con ‘depende’?”3 asks my husband, saying what I want to scream.

At that moment, the pilot brings the plane down. As the landing strip approaches, I see the runway’s not long enough. Within seconds we’d be in the Beagle Channel, drowning in the freezing water.

Then—

My stomach flips as the pilot brings the plane back up.

“Depende de lo rápido que caigamos en la pista.”4 says the pilot continuing the conversation as though I didn’t just vomit in his plane—which I did. Twice.

The pilot dives the plane down again, and this time, I close my eyes and prepare for the end. When the plane screeches and slides to a stop, I finally open my eyes—the front of the plane almost hangs over the cliff's edge.

“Estamos a salvo. Todo bien,” says the pilot.

Aside from the two small towns on Isla Navarino, I felt this was indeed the end of the world, or at least where civilization stops.

Remember when I told you all those stories about kabouters, Nolan?

Well, some people in Ushuaia believed creatures like gnomes and nymphs lived in the forests. It was easy to believe.

Here, I could roam without anything holding me back. Ever since childhood, I have loved the sense of this vastness, this freedom.

I first experienced it at my aunts' farms in The Pampas of Argentina, where my cousins and I could roam like wild horses. There was nothing but grasslands between me and the horizon. And when I was five, I had to leave it all behind.

Brasschaat, Antwerp, 1967

Belgium was a cage to me.

I left my cousins and aunts, trading their blend of warmth, kisses, tears, drama, and love for the unknown faction of my family. In Argentina, I had around ten cousins, and in Belgium, I met 30 more. Thirty cousins who spoke a language I didn’t. And while they mastered the art of hushing up and sitting still, I was used to running wild, firing rifles, and getting lost in daydreams.

The shock of these vast differences turned into an obsession during my youth.

All I yearned for was a ticket back to Argentina, and like a magnet, Tierra del Fuego drew me in.

I just had to find the right key to unlock me from my cage.

Running Off with a Stranger

Nolan

My father was a seafarer who scoffed at blade-wielding punks, frequented the rowdiest pubs in Antwerp as much as he did the opera, could name as many one-night-stands as he could philosophers, and the thought of a relationship never entered his mind until—

Luc

“The second I saw your mother, I knew she was the one. I was heading to a friend’s place for a drink. He was always up in his attic, so I climbed the steep stairs, pushed up on the door, and there she was. Her eyes, fiercely intelligent and filled with a sensuality I’d never experienced before. Her laugh, body, movements—it all drove me insane. The way she dressed—artsy, elegant, subtle, different—she didn’t try to be something. She was everything,” he says as he cuts a piece of steak, stealing my mother’s attention from the Okanagan Lake view with rolling arid mountains we’ve been lucky enough to call home.

My brother and I have heard him say this many times, but today is different. He found out he had prostate cancer a few months ago. His PSA levels are high. What exactly, I don't know. Numbers usually go in one ear and out the other with me. In this case, not knowing the details might be a defence mechanism.

Sitting on the patio with my little brother in my arms, the summer sun evaporates the water our father sprayed on the exposed aggregate concrete. It’s his way of keeping us cool.

“Was it love at first site for you as well, mama?” Yano asks.

My mother clutches my father’s hand as if the very act of release might let the tale slip away and dissipate into nothingness.

Antwerp, January 1981

Catalina

Stepping off the train in Antwerp, I was met with the scent of coffee and the echoes of footsteps and rumbling trains.

The glass vaulted ceiling cast a warm glow as I walked through the station. I took it all in for a moment, and I was about to leave when I heard—

"Oy, Caty."

It was your father. The week before, we met at a mutual friend's house and then danced the night away in the Gnoe, a rock n roll pub in the centre of Antwerp, stealing kisses in the dark.

"What are you doing here?"

I was too shocked to move.

"Waiting for you,” he said with a kiss.

Although I was taking my bachelor's degree in communications at the University of Brussels, I often visited Antwerp to see my family. Your father knew that but nothing else. I never told him my schedule or when I’d be in Antwerp.

"How did you know I'd be here?"

"A feeling."

Years later, I discovered that the feeling was less of a mystical coincidence than I thought. He had waited the entire day and watched several trains pass before I arrived.

He didn’t have to plan the next week. He just listened to the threads that pulled him towards Conscienceplein. The charming square in Antwerp is named after Hendrik Conscience, a key figure in the literary and national Flemish Renaissance of the 19th century. His statue, oxidized to a verdant hue, stands sentinel before Antwerp's repository library, home to a collection exceeding a million books.

On the opposite side of the plain, the Sint-Carolus Borromeuskerk is one of the many reminders of Peter Paul Rubens, who was commissioned to paint the intricate ceiling pieces. In 1968, some local artists closed it off with blocks of industrial ice, making it the first car-free square in Antwerp.

I already knew some of this, but Lucas described it with such passion and detail I understood why he called Antwerp his city.

What attracted me most was his pride when he spoke about his mother working as a librarian at the library of Antwerp. He didn’t seem drawn to feminism or any ism for that matter. Yet, the pain etched on his face as he disclosed his mother's resignation, compelled by societal expectations, said it all.

His spirit of rebellion drew me in, but it was his fervour for life’s subtleties that made time inconsequential. He honed in on the blooms, traced the fissures in the wall, dissected the interplay of sunlight, parsed the peculiarities of people, attended to the unspoken, and saw the world through eyes that banished my isolation. In surrendering to these intricacies and stillnesses of existence, minutes unfolded into hours, and hours stretched into days. It wasn’t a deceleration of time but rather a richness that filled its passage.

So, was it love at first sight?

I don’t know. But after these few dates, every single fibre in my body wanted to adventure with your father. A few weeks later, he told me he had planned a trip to the Bahamas and Jamaica. The only words my heart let out were, “Can I come with you?”

Marrying a Stranger: Papers & Pens.

April 28, 1981. 10:30 am.

Luc

Miracles happen at 10:30 am.

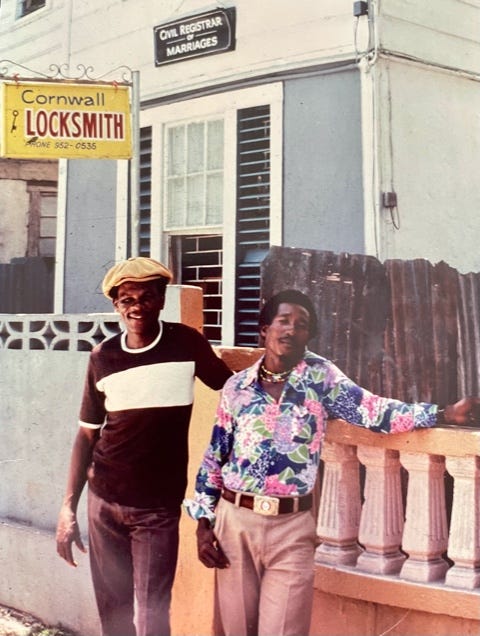

Gary and Alex stand in front of the locksmith which is on the floor below the Civil Register of Marriages' building. They are both dressed more stylishly than me, even though their freshly ironed pants are a size too big and cover the leather shoes.

"Di only ting mi fada lef' behind," Alex says, proudly pointing to his shoes.

Alex's Jamaican creole is even stronger than Gary's, but his low voice sucks me in and forces me to concentrate on every word.

"You guys look fantastic," Catalina replies, stroking Gary's back to straighten his shirt.

"Fi a beautiful lady, wi do anything."

"Alright, alright. Let's go," I say, taking Catalina's hand as we walk up the narrow staircase to the second floor that leads us to the Civil Register & Marriages office.

"Shall we?" Catalina says, opening the door to the office where a Jamaican official sits behind an impressive desk, wearing a suit with a stiff collar and French cuffs finished with golden cufflinks.

He bows his head and then looks paternalistically over his glasses as he says, "Welcome to Jamaica."

His gaze slides over Catalina's mauve long skirt to her dark purple top. Then he appraises me, my white pants and a slightly crumpled shirt that barely passes the stylish Jamaican's scrutiny.

"So, you are Lucas Jan Amandus—”

The second the name Amandus leaves his lips, Caty bursts out laughing.

“—Janssens.”

"Yes, sir."

The official squints, tapping his teeth with his index finger as he looks up at Catalina.

After another minute, she stops laughing, and whispers, “I didn’t know your middle name was Amandus.”

I smile at the official, wondering if he judges the trivialities we haven’t learned yet.

"And you want to marry this beautiful lady, Catalina Renata Thiers," he says.

"Yes, sir."

He licks his finger to flip another page in the marriage documents. I can read the letters from where I’m standing, but he doesn’t seem to decipher—or want to decipher—what I’ve written.

"Is it true that you stayed at the mansion of Lady Tiyana yesterday?" he croaks.

Must be a good customer of Lady Tiyana.1

In Catalina's dancing eyes, I see she rather enjoys the description of "mansion."

"Well, we will change the name to a good hotel in Montego Bay. We do have good hotels in Montego Bay."

"Thank you," Caty says as the tip of her nose curls with suppressed laughter.

The official’s eyes quiver as he gauges Alex and Gary.

"First, the witnesses must sign this document with their full names."

He motions Gary closer with a slight hand gesture; his eyes glued to the golden pen he hands Gary, making sure he won't replace it with the Bic nestled in the breast pocket of his floral shirt.

Then it's Alex's turn.

"I cyaa write," he says as he nervously fiddles with his pressed trousers.

"Just your full name, Alex," says the official.

Catalina encourages him with a supportive smile, and Alex leans over the desk. His hand trembles as it slowly moves across the paper. He signs his name and reads aloud, "Alex Ander Stone."

The official shoots an irritated look at Alex and says, "Your name is Al-ex-an-der.”

"My mother calls me Alex," he replies firmly.

"So your second name is Ander?" the official sighs.

"Alex Ander Stone."

"I hope he didn't write 'd' after Stone," I whisper to Catalina.

Unable to convince Alex Ander otherwise, the official connects Alex and Ander with an elegant curve, adding character to the marriage certificate.

Relieved that the Alex-Ander issue is resolved, the official asks if I can provide the rings.

"Well, uh, I don't have..." I stammer. "We thought—"

"Rings are boring, sir. We have necklaces. They come all the way from South Africa. Made of ostrich feathers."

Once again, the official's mouth falls open, and he repeats to himself the word "ostriches." Not gold, not silver, and God forbid, diamond necklaces, but jewellery made from the useless wings of ostriches.

"Yes, well… Okay. Dear Catalina, please put the necklace around your husband's neck."

She’s about to do as instructed, but—

"No, Catalina, the white necklace is for me. I've been wearing it for weeks." Then I silently add, "Besides, the black one is more expensive, seven dollars instead of five."

As the words leave my mouth, I realize how stupid I sound.

"Lucas, please put the necklace around your wife’s neck."

My wife?! The words buzz in my ears, and then it hits me—I am married.

With admiration, I look at my wife. She's like a bloom in the breeze, content to sway with the whims of all that transpires.

"Yow, dat cool, yuh a get married a Jamaica, man," Gary says. "Mi never a go forget dat."

"Yeah, man, so cool, so cool. Love a float inna di air.," Alex Ander sings.

"I wish you all the best for the future. Love each other, and enjoy a happy life," the official says.

It's clear that the man bears the weight of the spectacle, touched and yet relieved it’s over.

Or so he thinks.

"Sir, I still have one question," Catalina says, turning around at the door.

"Yes, dear Catalina, how can I help you?"

"Where can I get a divorce in Jamaica? You know, just in case.”

The office falls silent.

It's Easy to Marry in Jamaica: A proposal after six dates.

Catalina

We needed to leave the hollow tones of material ‘progress’ behind.

With metallic groans and grinding protests, the little Honda got us out of the fisherman's port-turned-resort town, Ocho Rios, and into the tropical sanctuary, Konoko Falls.

Around us, flowers in the deep green canopy burst forth in a riot of red, yellow, and purple hues. We inhaled their beauty and then took off our clothes, immersing ourselves in the refreshing embrace of the pools, born of the cascading waterfall. Limestone steps, worn by time, guided the waters' descent, creating a symphony of liquid echoes. Each droplet a fleeting testament to the ceaseless rhythm of nature.

After the scent of damp soil and tropical foliage filled us with energy, we decided to move on.

Your father drove through the mountains so we could see more of the island. Along the way, locals told us to stay on the paved main road and not drive off into the mountains, as it was dangerous—especially for “Whiteys.”

It was hard to believe.

Although Bob Marley was dying of cancer in Miami, his spirit was present throughout Jamaica. We were both aware of the political tensions, particularly between the two major political parties, the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) and the People's National Party (PNP). However, Bob Marley's music and philosophy of peace and unity seemed to transcend these political divisions.

Still, the locals warned us that if we went too deep into the forest, the chances of whiteys making it out alive were close to none. We heeded their advice.

As we drove further away from the tourist spots, I saw poverty I'd never seen. It was the first time I saw children with protruding bellies from malnourishment, making it difficult to believe the Rastafarian beliefs of equality and social justice were anything more than a pipe dream.

In the evening, we stopped at a bay, locally known as Glistering Waters or Luminous Lagoon. Here, microorganisms called dinoflagellates fill the water and emit a greenish glow when touched, leaving behind magical trails from wherever you swim.

We sat on the porch of our cabin and watched the orange sun drip over the Caribbean horizon. Then the stars came out, the infinity of the cosmos laughing above us as the fluorescent light show played its game.

It felt as though the energy of the cosmos aligned, and I was connecting to something beyond myself. The more we talked, the more I felt my soul was binding with another.

I was falling deeply in love.

Back in Montego Bay, we were discussing where to go next, and while browsing through the tourist brochures, I picked up one brochure that claimed, "It's easy to marry in Jamaica."

"Why don't we do that?" I asked Lucas.

On a practical level, it made sense. There was too much politics in Flanders surrounding weddings—there would be nothing but drama. Lucas came from a family full of atheists and socialists, and I came from a family full of conservative Catholics. His great-grandfather risked his life to house Jews, and my great-grandfather signed the agreements—

Well, you know how the story goes.

Anyway, the next morning, we went to the Civil Register of Marriages, above the town's locksmith, and asked Gary, a Jamaican man we befriended in Montego Bay, if he wanted to be one of our witnesses.

Lucas

"Yaw man, mi woulda love fi be yuh witness," Gary says. "An’ mi a go bring mi bredren Alex, too."

I look at Gary’s bare feet, wide with built-in soles from his callouses.

“I need to find nice shoes, man.”

And so, Gary brings us to the notorious Canterbury neighbourhood, where it immediately becomes clear that as a whitey couple without Gary, we have no chance of getting out unscathed.

“Ease up, mon. Dem people are mi fren dem. Yuh like Lambs Bread? Mi a go buy yuh some good Lambs Bread.”

“We have eaten, Gary,” Catalina snaps but stays close to his side.

“Lambsbread a di best ganja inna di world, yuh know. Happy stuff.”

Before I can clarify exactly what he means, he ducks under a tin roof held up by two concrete slabs, one of which we lean against. It is difficult to know if he has entered someone’s home, a communal yard, or is simply part of Canterbury’s maze. Within a minute, he reappears and hands me a brown paper bag with marijuana. He says it is enough for two weeks. To me, it looks like enough for a year. And to Caty, a lifetime.

“Where did you get this?” I ask.

“From yuh odda witness, Alex.”

Although I struggle to comprehend everything Gary says, I understand the witnesses are arranged—hopefully with shoes.

After Gary guides us out of Canterbury, Caty and I head to the cheap hotel we booked in an old colonial building in the heart of Montego Bay.

The only sign of life in the dark reception adorned with aged wooden furniture is the receptionist, an aging Jamaican beauty, exuding sensuality and rhythmically tapping the desk in front of her with long, manicured nails.

“Wah yuh waan?”

“A room for the night.”

She studies Catalina attentively with an approving glance.

“Tek di stairs, fus door on di lef’. Di bathroom is on di odda side a di hallway.”

It is a spacious room with a worn-out double bed that doesn’t exactly scream ‘Night before a wedding.’ It is humid, too. But not the type of moisture caused by the climate.

“I’m going to take a shower.”

“Strange hotel. Come back quickly.”

I feel refreshed after the shower and find Catalina sitting on the bed, her brows furrowed, like when she’s angry, studying, or sometimes just thinking about what to do next. I’d be worried if it weren’t for the smirk.

“Listen to this. The Jamaican lady asked me if I wanted to earn some money tonight.”

“Earn money?”

“Sex.”

Fuck. I brought my soon-to-be wife to a brothel the night before our wedding.

“Is this a brothel? That can’t be.”

“Oh yes, it is. Put your ear up against the wall over there.”

I walk toward the wall, cup my ear, and listen to exaggerated sex sounds.

“Maybe it’s another happy couple.”

“Sure, where the woman in the relationship earns twenty dollars an hour.”

I search for the best way to say sorry, but Catalina lets out her laugh that could make any of my problems disappear.

“Well, now you can say you slept in a brothel before you got married,” she says.

We cuddle up close. I feel the softness of her thighs and with my hand on her breast and my nose dug into the small of her neck, I fall asleep to the scent of her sweet skin and coconut-scented hair.

A Surprise Marriage Party

2:00 pm. The Wedding Party.

You don’t always get what you want. Sometimes, you get much more.

—Lucky people.

The centre table at My Brothers—the pub where we meet Gary—is covered with the flowers I found in my dream. On the terrace, gazing upon a beach, the table houses a bouquet of birds of paradise, their vivid orange sepals and blue petals unfurling from the spathe's beak-like embrace.

"What is going on?" Catalina asks, snapping me out of the flowers’ seduction.

"We havin' a little shindig for di Jamaican friends. No, for di friends of Jamaica, I mean," replies the owner of My Brothers.

"But we requested a table for four people."

"Dat right," he says, pointing to a table with the birds of paradise.

"Dat deh yuh table deh, mon. Yu get hitched a Jamaica, mon. Yu a real friend a Jamaica," Gary says, wrapping his arms around me and Catalina, my wife.

"Our table," Catalina stutters, grateful at our wild story taking a fairy tale turn.

"Bwoy, mi a starve till mi dead," Alex exclaims, putting Gary in a headlock. "Mi a murder mi food rival, yuh see!”

Once Gary gets out of Alex’s strong arms, he takes a seat across from Catalina, and Alex sits next to her. The spirit of Bob Marley serenades us with "Could You Be Loved" as the afternoon sun waltzes upon the sea.

Shortly after the song that will forever be etched into our hearts, four Red Stripes arrive along with two large bowls of goat curry.

"Mi granny cook di wickedest curry, mon," Gary says.

Catalina has a weakness for kids—the baby goat kind. When she holds a fork and knife, she does so with eloquence and style, but not today. She picks up a bone with some meat and sucks it clean while looking me straight in the eyes.

In my mind, everyone but Catalina disappears until—

"Your wife knows how to treat a man," Gary moans.

"What?" Catalina asks, but before anyone can answer, she looks under the table and realizes her foot is stroking the wrong leg.

Catalina almost chokes. "I am so sorry."

"Not me," Gary says with a wink.

As the orders of Red Stripes increase, so does the magic. Midway into the night, a group of young men appears armed with guitars, maracas, and tambourines.

"Wi bring love an' joy to unuh heart," says the man holding the guitar.

They stand around Catalina, all four of them, singing about the wonders the big bamboo performs in the bedroom. Their muscular bodies glisten in the late afternoon sun as they jam a style that reminds me of Harry Belafonte's infectious rhythms and smooth vocals but with spicier lyrics.

In the doorway, the owner stands, surveying everything with a smile. When he notices me looking his way, he winks.

What a wedding gift from a man we don't even know.

Catalina

April 29, 1981

The next day, we said goodbye to My Brothers to spend our honeymoon at Negril Beach, a seven-mile-long white-sand beach with crystal-clear, turquoise waters.

At the village entrance, a colossal tree loomed, and beneath its branches reclined an equally large woman, encircled by a cadre of robust and, I must admit, rather handsome Rastafarians.

"Hey, darlin', you got any smokes?"

Your father and I could immediately tell she wasn't from here or didn't grow up here. When she waved me over, I gave her one of my Camel cigarettes, which she gratefully accepted.

"What’s your name, sweetie?"

"Catalina."

"Hey, Caty, pleased to meet you," she said, startling me with the use of Caty— the name only my family and Lucas use. "Ah'm Miss Rose, and dem good-lookin' fellas ova there are mi boyfriends," She said, laughing and revealing her white teeth as she playfully squeezed one of the Rastafarian's legs.

"Where ya'll headin' to? The village?"

"Yes, indeed, we are looking for Miss Pat."

"My dear Caty, then we a go be neighbours. Just follow dis road for half a mile, and when you see a house with chillun playin' in da street, that's when you arrive at Miss Pat's. By the way, do you got rolling papers? This whole island is on strike. There are hardly any rolling papers or cigarettes about. I wish I neva lef Florida," She said, shifting her body to slump back against the tree.

"Okay, thank you, but I don't have any rolling paper. I'll see you around, Miss Rose."

"Bye, darlin'"

Following Miss Rose's directions, we strolled along tiny, simple wooden houses adorned with bougainvillea and young girls with beaded hair and the friendliest eyes.

"Do you know where Miss Pat lives?"

One of the girls pointed to a woman in loose, colourful attire and giggled before running away.

"Hi, are you Miss Pat?"

We approached the woman sitting on a step leading up to a wide veranda that wrapped around the entire light blue house. It seemed large enough to house several people comfortably.

"Yeah, dat’s me, beautiful."

"Do you happen to have a room, Miss Pat?"

"Yeah, I do. How long yuh a go stay?"

"Five nights."

"Aight, dat be twenty dolla a night. Wha part yuh a come from?”

"We're from Belgium and just got married in Montego Bay. This is our honeymoon."

"Yuh get married a Jamaica? Well den, yuh can stay for twelve dolla a night, and I will go cook you up some dinners. Dinner tonight at six o'clock."

The price was indeed a gift for the room. The wood on the walls and floors was old and scratched but added a rustic charm. And at least we didn’t end up in another brothel.

After a refreshing shower, we walked out onto the patio and found a fit Jamaican man with an American baseball cap in the hammock right outside our room.

"Aftanoon, yuh mind if mi tek a smoke on di patio?"

It was a large marijuana joint wrapped in brown wrapping paper.

"For you," he said.

Rejecting it seemed unnatural. I took a small inhale from the cigar-looking thing, Lucas took a few more, and soon after, the world turned into a comedy show.

Suddenly we heard a familiar voice.

"Hey, yuh have any ciggies?"

It was Miss Rose, walking towards towards Miss Pat and I.

A dozen or so children ran back and forth from the yard towards the three of us on the patio, urging Miss Pat to give them a piece of pineapple or banana.

"Are those your children, Miss Pat?"

"All di children of the street a mi children, Catalina," Miss Pat laughed. "Dis ya place a one big community. Wi love an' feed each odder pickney. Di young maddas in di resorts, so dem pickney come to me. Woman dem cook, woman dem clean, woman dem do everything while man dem smoke funny cigarettes," She said with an accusing look at your father and the Jamaican in the hammock.

Later that night, Miss Pat invited us to eat Escovitch fish, a typical Jamaican dish with grilled red snapper topped with a savoury and tangy mixture of scotch bonnets, bell peppers, onions, and red wine vinegar. To be honest, I wouldn't have known any of that at the time. It just tasted like good, home-cooked food.

When we finished the meal, your father went to the hammock, and I ordered two more Red Stripes for Miss Pat and me.

"The fish was really delicious, Miss Pat."

"Red snapper a one good fish. An' as a married woman, yuh haffi learn to cook. Yuh cook, Catalina?"

"Well, I like to eat. Lucas is the cook."

"So yuh man can cook, dat already someting. But a di woman haffi bring love inna di kitchen. Yuh haffi bring love inna di bedroom an' love inna di kitchen."

Well, one of those I was confident in.

"Do you love your husband, Catalina?"

"To be honest, we just met. But I've had nights and feelings with him I've never experienced with anyone before. He's full of life and loves the small details of everything, just like I do. There's nobody I'd rather travel with," I said, feeling how proud and happy I was to have him as my husband. "He likes so many things. He likes butterflies, flowers, food, and everyone seems friendlier when he's around…But he can't dance. At least, not like the men in Jamaica."

"Oh honey, but can him perform?"

I blushed at the question, but I guess my eyes said it all.

"Dat good, baby. A woman need weh she need. But mek him know fi no smoke dat funny stuff. Tell him all di things him like fi hear, but just do yuh own ting. Yuh a di boss. Mek dem think dem a di boss, but don't fuhget dat. An' bein' wid a good man, Catalina, is like a journey. A journey weh neva end."

She was the first woman I really spoke to since getting married. As you know, I usually don't like women. I find them boring and hung up on things that don't matter. Maybe it was the milieu of women I came in contact with in Belgium, and Miss Prat was the opposite. She had no time for… bullshit. You know, I don't curse often, but that's the word. There was something maternal and wise about her. Maybe it was the stern and loving way she played with those children. Maybe it was her tired, knowing eyes that sprang to life when she laughed. Whatever it was, she was the person I was meant to speak with at that moment.

"I will never forget you."

Her smile was a silent affirmation of the truth in my words. The unspoken understanding lingered between us—our paths would never cross again. There was no need to write down names or addresses for letters. To me, people had always been chapters, transient narratives intersecting with mine. They'd come into my life, and then one of us would leave. That's what I learned as a little girl.

Then she winked at me, left the small dining room, and sang the song playing in our hearts.

We're jammin'

I wanna jam it wid yuh

We're jammin' jammin'

And I hope yuh like jammin' too.

The USA Was a Stepping Stone

Here, I stand in the fluorescent-lit corridor of bureaucracy in Miami airport, facing an immigration officer who could easily double as a drill sergeant. As he inspects my passport with the precision of a surgeon, I wonder if I've unwittingly stumbled onto the set of a military-themed reality show.

“Why are you staying in ‘Merica?” he asks.

“I’m not.”

“You’re in the United States of America, son. So, I’ll ask you again. What are you doing in America?”

“I have a layover on my way to Argentina.”

“A layover on the way to where?”

“Argentina.”

“Ar-gen-tina.”

“Yes.”

“You have a layover here on the way to Argentina?”

“That’s what I said.”

“And exactly what do you plan on doing in America on your way to Argentina?”

“Nothing. If there were a flight where I wouldn’t have to step foot in this country, I would have taken it.”

The immigration officer is so taken aback that he hands back my passport and lets me catch my plane.

Nolan

I was twelve years old when I heard this story from my father, but it didn’t come as a surprise. People who had never left Canada or the United States often credited Jesus for my parent’s survival in godforsaken countries. Instead of fearing the country of Africa (as many of these people referred to it) and those cocaine-ridden death traps below Mexico (again, not my words), I was wary of the USA.

My parents had slept in Latin American ghettos and avoided death by luck dozens of times, but when I asked my mother where she had been most afraid in her life, the answer was New Orleans.

Catalina

We saw my father’s corporate apartment in New Orleans as a stepping stone to Costa Rica.

As a sailor on merchant ships, your father wasn’t obliged to do his one-year military service in Belgium. But he wasn’t a sailor anymore, so he had to stay out of Europe for the next five years if he wanted to avoid his military service. For your father and I, staying out of Europe for five years to avoid military service was worth it. And what better place than Costa Rica, a country without an army?

However, staying in New Orleans wasn't precisely aligned with our pacifist ideals.

I was all alone because your father had gone to Costa Rica to check it out beforehand. Since he was searching for places we could afford (which wasn’t much), he didn't have a set itinerary, and I had no way to get a hold of him.

I sat by the phone all night, craving his voice. Instead, I received muffled telephone calls with strange, distorted mumbles three days in a row. Between the heavy breathing, shrieks, and sudden pauses, I couldn’t make out any clear threats, but it was enough to bring me into a surreal state of fear. Sleep-deprived, I started to imagine...

As a visual artist, the best way I can describe the feeling is with a painting.

I didn't select The Death of Marat II by Edvard Munch for the murderess it depicted, but rather because I found myself stripped bare, vulnerable to the unrelenting presence of death looming ever closer. In a world where death denial shadows every step, the canvas spoke to my raw exposure to my mortality.

The third morning, I finally built up the courage to go outside to my car so I could get more food and experience life in downtown New Orleans. But to my horror, I saw somebody stuck match sticks in the doors' keyholes.

Although nothing physical happened, these mind games went on for three weeks until I finally got a call from Lucas.

He rented an apartment in the capital, San Jose, and was waiting for me to join. I was ready to get the hell out of America.

Two weeks earlier…

Luc

The Mississippi River takes a sharp turn where the French Quarter stands, a historic community translating the history of the US into jazzy undertones. Every drop of water from Lake Itasca in Minnesota, where the Mississippi River originates, mixes with the sweat and blood of the population, as well as the melting snow and subtropical rains from the ten states through which this mighty river winds its way.

Here, at the deepest point of the river, Algiers Point, 60 meters deep, the fascinating city of New Orleans emerges, squeezed between the river and Lake Pontchartrain, fighting against floods and sociopolitical injustices.

If all the sorrow of the African slaves and the decimated Native American population were collected in a lake, it would be Lake Itasca, just big enough to channel those tears into the second-largest river in North America, with the ultimate goal of reaching the Gulf of Mexico.

Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana—states that should be ashamed of their racist past and the glorification of church and dollar. Instead, they voted for Ronald Reagan, who, along with Margaret Thatcher, gave the starting signal for unbridled capitalism and unlimited greed. The beginning of—

A large African-American man sits beside me, pulling me from my thoughts. He wears a baseball cap with the Saints logo, the local American football team. Sharing my opinion about American football is the fastest way to die, or so I think. Instead, I sit quietly, observing the river with my thoughts in silence.

"You 'sposed to be scared of me."

"Sorry, why?" I say, continuing to roll my cigarette.

"Cause you on the wrong side o' da river."

"Perhaps. Yesterday I was on the right side of the river, thoroughly enjoying Mardi Gras, the flashing of boobs when people yelled, 'Show your teets, show your teets’.”

When I notice his smile, I know to continue.

"And this side of the river is far enough from the French Quarter to heal my hangover."

He laughs and extends his hand. I shake his bear paw and look into his eyes, a friendly brown, carrying the weight of a thousand unspoken stories, each tale etched into the creases that radiated from their corners like the delicate fissures in the parched earth.

"Sorry, son, I ain't familiar with dat side o' da river. I ain't welcome there. But it sounds like a good time. Where you hailin' from?"

"Belgium. You know, squeezed between Netherlands, France, and Germany."

I'm used to having to locate Belgium on a map and give further explanations, but then he says, "I know 'bout Belgium. My grandad passed there durin' the war. He had the choice to be killed by a German or a redneck from Louisiana. He preferred the bullet to the hanging tree."

Silence.

"First time here?" he asks.

"No, three years ago, I was at the wheel of an enormous cargo vessel, steering the ship from the delta to Baton Rouge. Super scary. I mean, the American pilots were. Holy shit."

"And now?"

"I'm here with my wife and father-in-law, who promised me a job in the offshore oil business. But that seems like a pipe dream."

"So, back to ships?"

My father-in-law suggested managing his new plant in Aberdeen, Scotland, but I sensed his business partners didn't want to have the "eye of Moscow" in their vicinity. So, yes, going back to supply vessels in South Africa or Canada is certainly the most rational solution.

Unfortunately, I am not rational, and I belong to the species of apes who first jump into the river to find out if they can swim, so all I say is, "A Mexican friend told me about Costa Rica. I think I’ll try the little paradise in the midst of hell."

As you can tell, a lot of work went into telling these stories. If you want to read more, please become a paid subscriber. Founding members can also request a signed paperback. Remember, all my work is published on Ghost, a decentralized, non-profit, and carbon-neutral platform—free from VC funding and the grip of technofeudal lords.

I don’t use algorithms to hijack your attention.

My work can only exist if you share and support it.

Butterflies

Limon, Costa Rica

December 2, 1982

Lucas

The blood spread across the ceiling is ample forewarning to turn the fan off. Our room has a double bed, a little nightstand, and a pendant lamp suspended by a frayed wire, dangling precariously close to the two clammy pillows.